As is the case with epidemiologists, the fundamental challenge faced by economists — and a root cause of many disagreements in the field — is our limited ability to run experiments. If we could randomize policy decisions and then observe what happens to the economy and people’s lives, we would be able to get a precise understanding of how the economy works and how to improve policy. But the practical and ethical costs of such experiments preclude this sort of approach. (Surely we don’t want to create more financial crises just to understand how they work.)

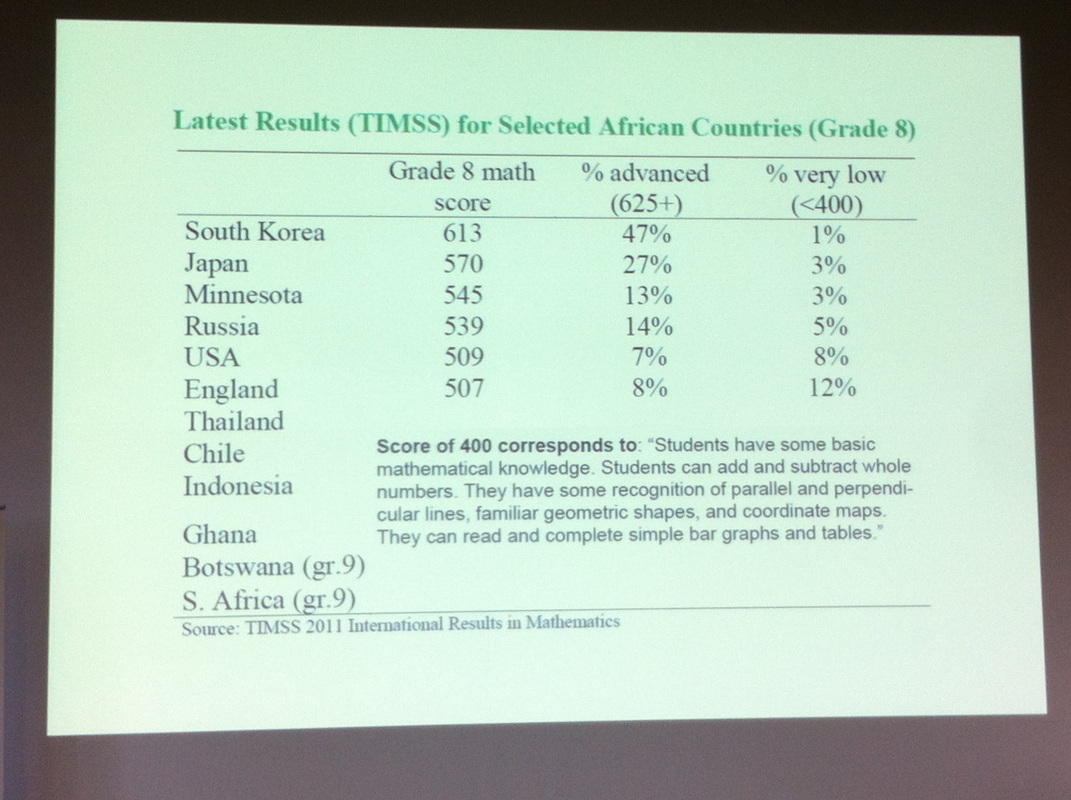

Hat tip: COCO (a real scientist)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed