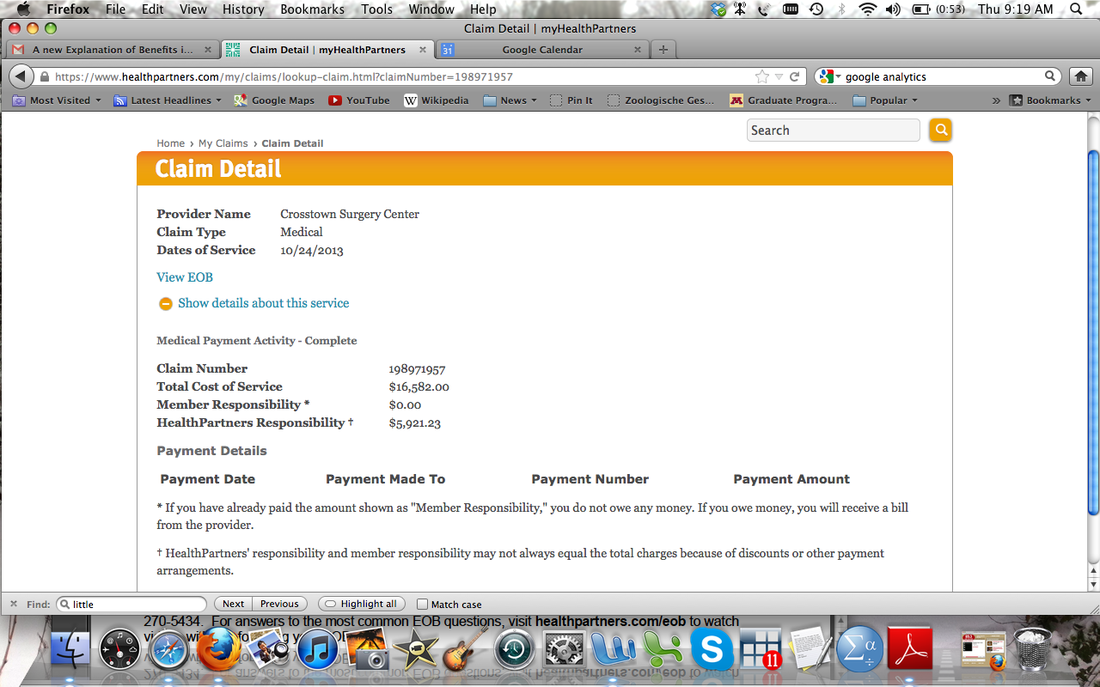

Similar to my study, the authors use a randomized control trial to measure the impact of husbands involvement in decisions about whether or not to adopt contraceptives. In contrast to my study, the Zambian health worker only visits homes a single time and gives a voucher for free injectable contraceptives (my intervention is longer and contraceptives are already free Tanzania). Women who receive the voucher alone (without their husbands) have the option of adopting contraceptives discretely; women who receive the voucher together with their husbands have a clearer path towards some form of family planning communication. Men in the Couples treatment (e.g. receive together) are essentially given veto power: they are a part of the discussion about the availability of contraceptives and can choose to express their approval, be part of the contraceptive adoption process, prohibit the stuff or be a stick in the mud (among other options). And because men in these samples typically have more bargaining power within the household (economist speak for women not empowered), this sort of inclusion of husbands translates into the power to obstruct.

A somewhat unsurprising discussion in this paper is about the trade-offs between privately improving a woman's set of choices (and gaining utility), while possibly lowering the value of the marriage by the addition of secrecy (the "conjugal value of the marriage"). And in my own study, I've heard some women admit to the short-term benefits of concealed used of contraceptives while bemoaning the risks of secrecy and poor communication in their marriage. In other news, these women tend to have inattentive and unhelpful husbands.

One thing that Ashraf et al. seem to overlook, however, is the possibility of changing the psycho-social cost (economist speak for anxiety) of using contraceptives.

We do find that [women in the Individual treatment, who had an opportunity to use contraceptives without their husband's approval] experienced a significant reduction in happiness, health and ease of mind compared to those in the Couple treatment. This suggests a longer-term psycho-social cost to concealable contraceptives that can be mitigated by spousal involvement.

While involving husbands in the dialogue over family planning is one way to reduce the burden of secrecy, the elephant in the journal article is that birth control carries this weight of anxiety because it is not socially acceptable in these places. The type of husband whose wife is seriously considering concealed contraceptives is not exactly a well-educated progressive male feminist. He resides in the space where social acceptance matters, traditional gender and tribal roles dominate and mis-education (especially with regards to medicine and healthcare) is rampant.

In fact, in their large sample, some men who even expressively did not want to have a child in the next two years simultaneously discouraged their wives from using contraceptives, thereby increasing inefficient outcomes (which, in this case, is economist speak for unwanted births). This is not just miscalculated costs or utility, this is something bigger.

Despite my training as an economist, I cannot deny that the psycho-social cost of adopting contraceptives (concealed or not) can be reduced by fuzzy things like social change. Of course, I also acknowledge the standard fertility determinants of microeconomics. But, my work with community health workers in rural Tanzania has given me renewed hope in training, education and development as vehicles to adjust gender norms and create institutional social change. Social change is hard to measure and harder to implement, but when it is done well, the change is undeniable. Poor people's fertility choices may be easier to digest through a simple microeconomic lens, but to study these decisions without at least some acknowledgement of the larger social factors dominating individual action like sexism, culture and social norms is to overlook the greater implications of this research.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed