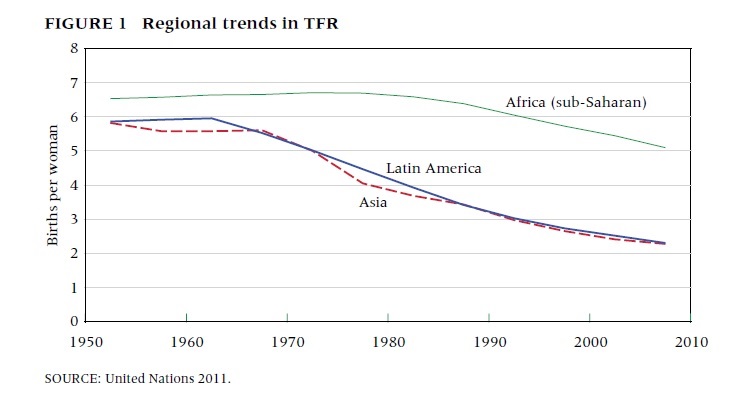

Bongaarts and Casterline in Population and Development Review explore whether sub-Saharan Africa's fertility is systematically different from the rest of the world, a theory first posited by Caldwell (1992). The authors reject Caldwell's hypothesis that these countries are experiencing a different type of transition in which declines in fertility are occurring at older ages. However, they do confirm some unique characteristics of sub-Saharan Africa's fertility experience. First of all, in many regions, the decrease in Total Fertility Rate (TFR) has stalled, in contrast to the pattern of steep TFR decline in the earliest stages of demographic transitions in Latin American and Asia. And secondly, the small decreases in TFR are mostly driven by larger birth intervals rather than a desire for smaller families.

Except Rwanda. The Rwandan DHS shows an unusual pattern in which unmet need (as defined by women who do not want to get pregnant and are not using contraception) declined by nearly a half between 2005 and 2010, to which the authors credit the invigoration of a national family planning program. Contraceptives use more than doubled between 2005 and 2010. This stands in stark contrast to other sub-Saharan countries (e.g. Ghana, Burkina Faso, Kenya and Nigeria) where use of contraceptives has basically stalled since the mid-1990s.

What this paper doesn't answer is how the drivers of unmet need (e.g. lack of knowledge of contraceptive methods and supply; low quality and limited availability of family planning services; cost of methods in travel and time; familial objections and concerns about acceptability) that are propping up that green curve, can be fixed.

Except Rwanda. The Rwandan DHS shows an unusual pattern in which unmet need (as defined by women who do not want to get pregnant and are not using contraception) declined by nearly a half between 2005 and 2010, to which the authors credit the invigoration of a national family planning program. Contraceptives use more than doubled between 2005 and 2010. This stands in stark contrast to other sub-Saharan countries (e.g. Ghana, Burkina Faso, Kenya and Nigeria) where use of contraceptives has basically stalled since the mid-1990s.

What this paper doesn't answer is how the drivers of unmet need (e.g. lack of knowledge of contraceptive methods and supply; low quality and limited availability of family planning services; cost of methods in travel and time; familial objections and concerns about acceptability) that are propping up that green curve, can be fixed.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed