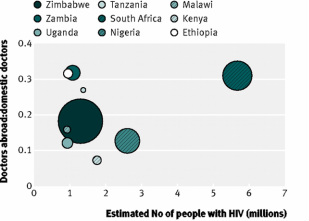

Loss of doctors to destination countries, compared with burden of HIV in nine African source countries. Size of each bubble represents ratio of estimated compounded lost investment over gross domestic product, and y axis corresponds to ratio of doctors working in target countries and doctors currently working domestically.

Do developed countries drain all the health workers trained abroad? And what is the impact of this?

Michael Clemens of CGE wrote a feisty response on Blattman's blog to the notion that doctors are being stolen from poor countries. Additionally, Katie Leach-Kemon, at IHME, sent me a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis of human capital loss of doctors trained in Africa and working in developed countries. I'm trying to synthesize the two.

Clemens is certainly right that medical staff are perfectly active agents that have just as much right to emigrate as any other expat. The question remains, however, whether or not Clemens' $6,000 per year in remittances sent from the US to Africa is actually any legitimate compensation for losing a health worker. This human capital analysis indicates that the cost of educating a health worker in their home countries, across various African countries, varies from $21,000 to $59,000. These numbers grow significantly when you consider loss of return on investment (without consideration for remittances). However, its difficult to compare costs and benefits when human capital costs are public and remittances are sent to private family members.

Additionally, the human capital analysis assumes that health workers leave their home country immediately following training, while Clemens finds the average African-trained member of the American Medical Association left his or her home country well over five years after earning their MD. Does this make up for the loss of human capital? Probably not.

The human capital analysis concludes that because they are benefiting from medical staff trained abroad, "destination countries should consider investing in measurable training for source countries and strengthening of their health systems." While investing in health care human capital is beneficial, I'm not sure this is the most efficient solution. In the U.S., some medical schools provide incenstives for doctors to work in rural regions or states though medical school loan forgiveness. Some market mechanisms in developing countries may provide more reasons and incentives for and African-trained doctor to stay in Africa and fulfill that return on investment.

Michael Clemens of CGE wrote a feisty response on Blattman's blog to the notion that doctors are being stolen from poor countries. Additionally, Katie Leach-Kemon, at IHME, sent me a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis of human capital loss of doctors trained in Africa and working in developed countries. I'm trying to synthesize the two.

Clemens is certainly right that medical staff are perfectly active agents that have just as much right to emigrate as any other expat. The question remains, however, whether or not Clemens' $6,000 per year in remittances sent from the US to Africa is actually any legitimate compensation for losing a health worker. This human capital analysis indicates that the cost of educating a health worker in their home countries, across various African countries, varies from $21,000 to $59,000. These numbers grow significantly when you consider loss of return on investment (without consideration for remittances). However, its difficult to compare costs and benefits when human capital costs are public and remittances are sent to private family members.

Additionally, the human capital analysis assumes that health workers leave their home country immediately following training, while Clemens finds the average African-trained member of the American Medical Association left his or her home country well over five years after earning their MD. Does this make up for the loss of human capital? Probably not.

The human capital analysis concludes that because they are benefiting from medical staff trained abroad, "destination countries should consider investing in measurable training for source countries and strengthening of their health systems." While investing in health care human capital is beneficial, I'm not sure this is the most efficient solution. In the U.S., some medical schools provide incenstives for doctors to work in rural regions or states though medical school loan forgiveness. Some market mechanisms in developing countries may provide more reasons and incentives for and African-trained doctor to stay in Africa and fulfill that return on investment.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed