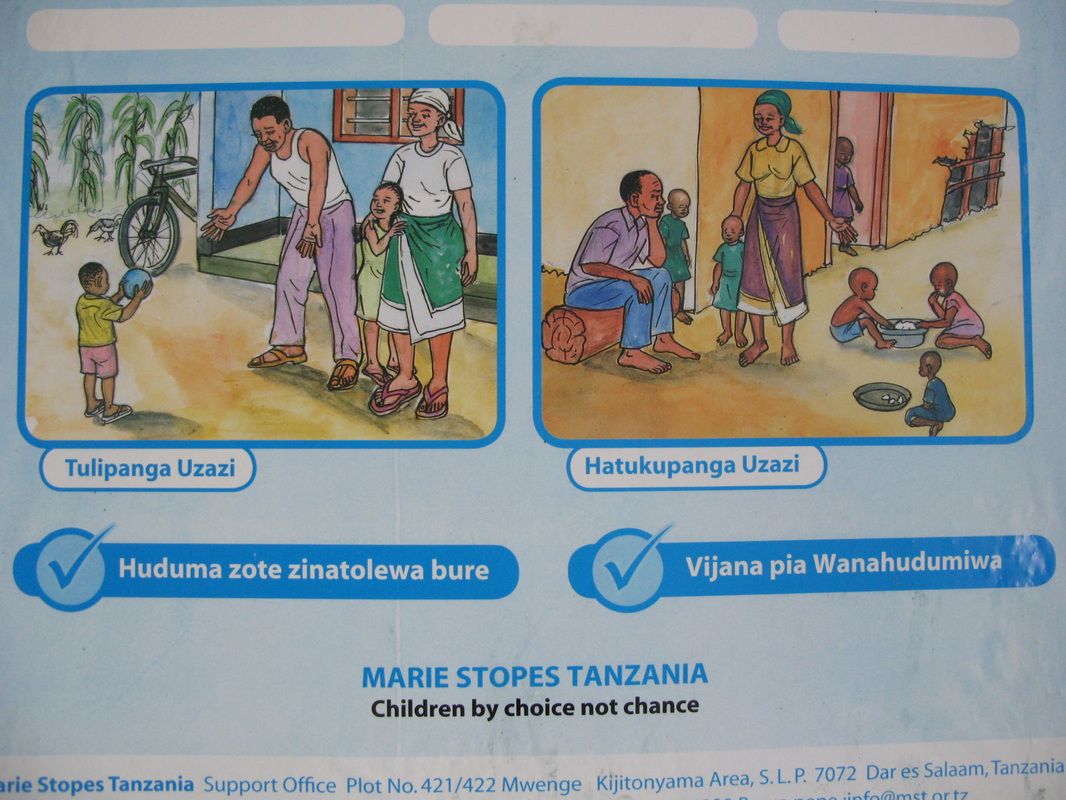

Having spoken to a lot of women who seem legitimately interested in family planning (although I have also developed a strong social bias detector), I'm more aware of the logistical challenges that Mama from Mwajidalala village might actually face in adopting contraceptives. Dispensaries are fairly well stocked and family planning is almost entirely free. For the most part, the Ministry of Health staff appears well-trained and dedicated to their work.

The big hold up to access is combination between timing and distance. It's Ministry of Health policy that women cannot start on a contraceptive unless 1) they've had a check-up to ensure that the method is the right one and 2) the big logistical challenge, that they are on their period on the day they visit the clinic. Both of these policies are standard health procedures and fairly consistent with my experiences in the states. The methodology behind timing adoption with current menstruation is to be absolutely sure that Mama from Mwajidalala isn't pregnant.

However, the crucial information of 1) and 2) from above are not very well-known (although the CBDs in my study are very hopefully spreading the word). If Mama from Mwajidalala, who works up the gumption to leave her work in the cotton fields for a day and walk to the closest dispensary, four hours away, she might finally arrive and be told that she hasn't come on the right day of the month. This is obviously frustrating and time consuming for Mama from Mwajidalala, so she might gives up there.

There's hope with the mobile clinics- the Ministry of Health's way of addressing the fact that villages and subvillages are so spread out in Meatu. The health center and district hospital operate a schedule of visits to each village every month for outreach. But for Mama from Mwajidalala, the timing is again a challenge since the mobile clinic schedule likely does not coincide with her menstrual schedule. The probability of Mama being able to adopt contraceptives from the mobile clinic, is about 5/30, or 1/6.

All this timing and access challenge makes me grateful that my intervention lasts a full year. But even this feels too short.

The big hold up to access is combination between timing and distance. It's Ministry of Health policy that women cannot start on a contraceptive unless 1) they've had a check-up to ensure that the method is the right one and 2) the big logistical challenge, that they are on their period on the day they visit the clinic. Both of these policies are standard health procedures and fairly consistent with my experiences in the states. The methodology behind timing adoption with current menstruation is to be absolutely sure that Mama from Mwajidalala isn't pregnant.

However, the crucial information of 1) and 2) from above are not very well-known (although the CBDs in my study are very hopefully spreading the word). If Mama from Mwajidalala, who works up the gumption to leave her work in the cotton fields for a day and walk to the closest dispensary, four hours away, she might finally arrive and be told that she hasn't come on the right day of the month. This is obviously frustrating and time consuming for Mama from Mwajidalala, so she might gives up there.

There's hope with the mobile clinics- the Ministry of Health's way of addressing the fact that villages and subvillages are so spread out in Meatu. The health center and district hospital operate a schedule of visits to each village every month for outreach. But for Mama from Mwajidalala, the timing is again a challenge since the mobile clinic schedule likely does not coincide with her menstrual schedule. The probability of Mama being able to adopt contraceptives from the mobile clinic, is about 5/30, or 1/6.

All this timing and access challenge makes me grateful that my intervention lasts a full year. But even this feels too short.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed